Disunity results in a weakened movement

Our Civil Society Conflict Survey reveals a significant lack of skills and resources to effectively prevent and manage conflicts severely undermines the sector’s impact.

While extensive research and support exist on workplace conflict in the corporate sector, relatively limited attention has been paid to its dynamics in civil society. By comparison with the private sector, civil society is woefully unprepared to manage internal conflict.

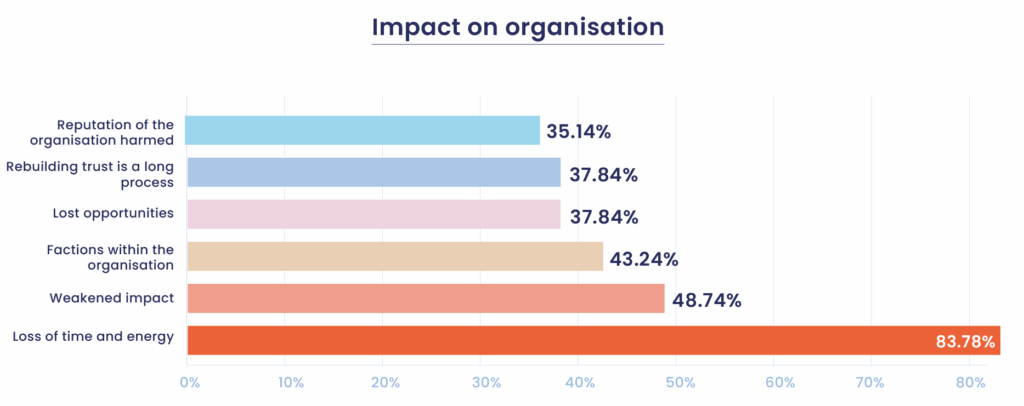

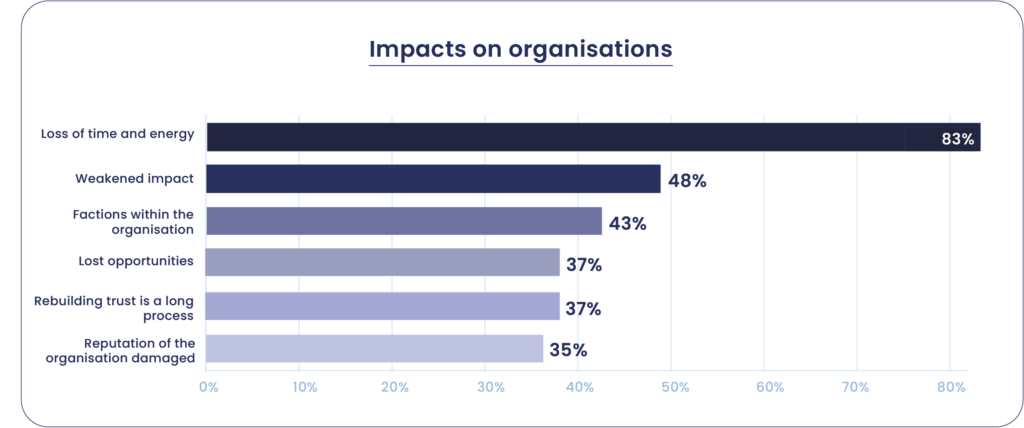

Conflicts in organisations

The graph below highlights the impacts of conflicts within and among civil society organisations, as revealed by the Civil Society Conflict Survey.

At the organisational level, conflict was described as a drain on time, energy, and resources (83%), with the majority of respondents also reporting weakened impact (48%), and reputational damage Another ubiquitous problem was the development of factions within organisations (43%), leading to fragmented teams. The time-consuming nature of rebuilding trust (37%), which often far outlasts the conflict itself, was also ubiquitous. Additionally, missed opportunities—whether in funding, partnerships, or strategic initiatives — were frequently listed as tangible losses.

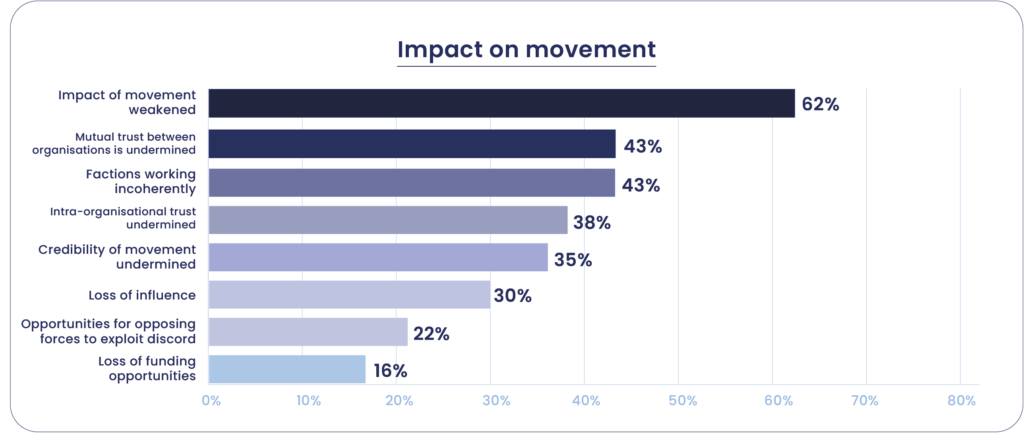

The unintended impact of conflicts on the movement

The graph below highlights the impacts of conflicts within and among civil society organisations.

When examining the impacts of conflict on the effectiveness of the broader movement, responses highlighted a pattern of incoherence and fragmentation. Many referred to the weakening of the movement’s collective impact (62%), with some specifically citing loss of influence in advocacy spaces or policymaking forums. Credibility was often said to be undermined, particularly when conflicts played out publicly or remained unresolved for extended periods. Several responses emphasised how conflict created opportunities for external forces to exploit divisions, which further weakened their movements’ cohesion and strategic direction.

Importantly, some responses contextualised conflicts as being driven by underlying structural issues, including neo-colonial mindsets, inequitable power dynamics, and contradictions between formal values and internal practices. These deeper sources of conflict suggest that technical fixes alone may not be enough; what’s needed are systemic changes in how individuals and organisations relate to each other.

People’s experience of conflict

A significant part of the survey was devoted to unpacking respondents’ experiences of conflicts and the lessons they had learned from them.

When asked what should be prioritised in the immediate aftermath of a conflict between organisations, a majority (55%) ranked “repairing internal relationships” as their top priority. This suggests that restoring trust and cohesion within one’s own team is considered foundational before addressing external disputes.

The most commonly cited barrier to entering a resolution process was “doubt that it can work,” which was reported by over 60% of respondents. This lack of faith in resolution processes often stemmed from previous failed attempts or the absence of trustworthy facilitation mechanisms. Other frequent barriers included “uncertainty about who will support your position” (around 50%) and “time or capacity constraints” (approx. 50%).

Respondents widely believed that long-lasting conflicts endure due to a lack of systemic change. Nearly 66% referenced a belief that “people/systems will not change” as the leading cause of prolonged conflict. Others pointed to loss of autonomy through compromise, and about 33% noted that “remaining in conflict can sometimes preserve power or strategic advantage”.

Perhaps most strikingly, the results showed that many conflicts are prolonged, with over 40% describing conflicts that lasted more than one year, and several reporting durations of 3–5 years or more. Only about 20% experienced conflicts shorter than a year. This highlights the long-term nature of civil society disputes, particularly those rooted in governance, leadership, or strategic alignment.

The long unattended pathway to resolution

One of the most striking insights yielded by the survey was the paucity of effective conflict management resources in the civil society sphere. It was reported that conflicts often remained unresolved or were “worked around” rather than being properly addressed. Approximately 49% of respondents said their conflict was only resolved when one or more individuals left the organisation, often because leadership failed to intervene or because the conflict became too toxic to repair. Respondents emphasised the value of transparency, active listening, and structured processes. Still, the more ubiquitous practices of avoidance, delaying engagement, or ignoring the conflict were consistently described as harmful.

Over 82% of respondents reported that rebuilding trust in the aftermath of a conflict was a long and challenging process, often taking years. Others described a lasting sense of caution or avoidance, especially around sensitive issues or past points of disagreement, indicating that even when the formal conflict ends, psychological impacts and behavioural patterns often persist.

The need for more effective conflict management resources

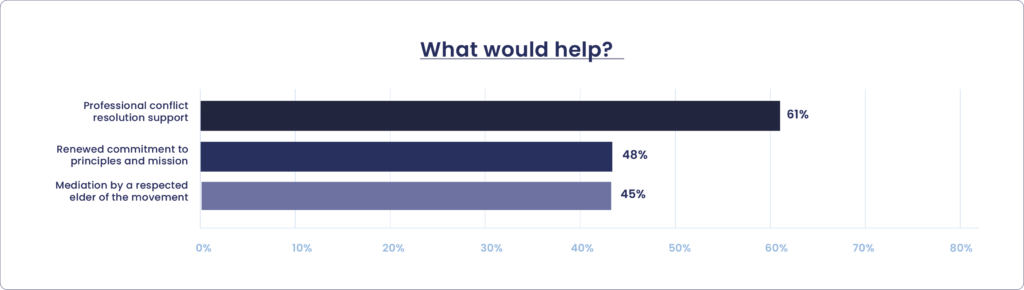

The survey revealed a pressing need for dedicated conflict management support in civil society, with over 60% affirming that such resources would make their organisations more effective.

Across all responses, there was consensus that improved conflict resolution would:

- Reduce individual stress and improve morale

- Bring greater stability to the organisation

- Make decision-making more effective

- Strengthen collaborations between movements

- Enhance mission impact

Conclusion

Conflict within NGOs and social movements is widely regarded as a significant impediment to effectiveness, not only internally but also across entire ecosystems of civil society work. The emotional, professional, and strategic toll is profound. Across the board, respondents emphasised the need for improved conflict resolution mechanisms, more effective leadership, and more equitable practices to mitigate the destructive consequences of unresolved tensions.

There is a clear need for better conflict management in NGOs and social movements.